Young authors fly

It starts with an email out of nowhere that says something like Hello, would you come to Someplace Far Away to teach kids and the voice in my head barks SPAM and I always have to pause on the delete button because I don't always feel as lucky as an email like that would indicate. I'm usually here by the woodstove worrying about whatever's supposed to come next, feeling isolated by the country, and The Country, and the weather, and the boundaries of my brain. And then boom: HELLO.

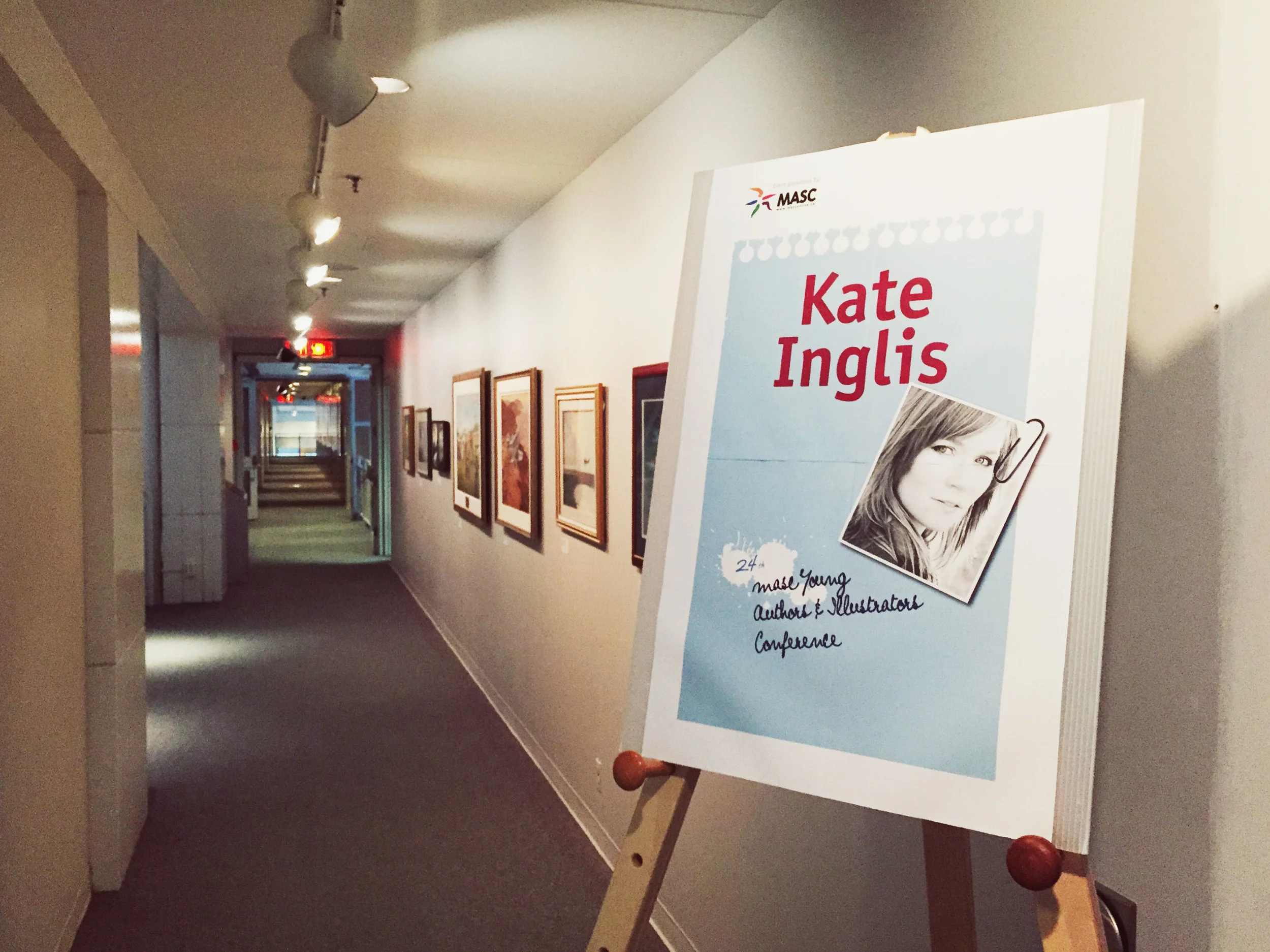

I got on a plane and this time, I landed in the capital city of Canada for Ottawa's MASC Young Illustrators & Authors Conference. I drove past Parliament Hill, and threw a few rotten eggs out the window at Prime Minister Harper's house. I missed. I told author Tim Wynne-Jones to hit the gas, and we evaded the RCMP in a chase that ensued but only after our car flew over a cliff with an unfurled umbrella to save us, like Paddington Bear or Pee Wee Herman. In mid-air, somebody shouted THE AAARTS! and the sky exploded like a wall of paintball splooshes and when we landed, we were all a million colours.

Being around kids—especially 600 over three days—makes you tell tall tales. The taller, the better.

Unlike in Labrador, where artists were ferried around in tiny planes to Innu and Inuit outports, this event trucked students in by apparent dozens and we stayed put in perhaps the best workshop space I've ever seen—Ottawa's Canada Aviation & Space Museum. The moment I walked into the building, I saw a great black hulk staring me down from across the hangar and it was, indeed—as I'd recognized with a gasp—my grampa's plane.

It was the great British bomber, the legendary Lancaster, dwarfing the Messerschmitt and the Spitfire and everything else that sat parked in the lee of its wingspan. I'd never seen one before. We had the run of the place, so every morning on my way past Chris Hadfield's space suit down the hallway of astronauts to my workshop room, I'd tiptoe underneath the fuselage and press my palm to its belly or a tire or a bomb and whisper Hello, chums and I swear they whispered back.

'Loaded, 1944.' From my grampa's photos over four tours of duty.

Being on such sacred ground—along with an ornithopter (a human-powered glider that flies like a bird, with flapping wings), a crashed turn-of-the-century bush plane, and the skeletons of the very first cloth-covered means of flight—was imagination food. Every day, I ordered the kids out onto the floor in search of stories.

There were mechanical dragons and thieves. There was a German defector, a wolf pack, a storm. A girl crash-landed, her bush plane swallowed up into the deep muck of a lake, and she emerged when they found her fifty years later. She had grown gills and gone wild. They all stood up one by one and read out loud and I stood there with my hand over my mouth, smiling so big.

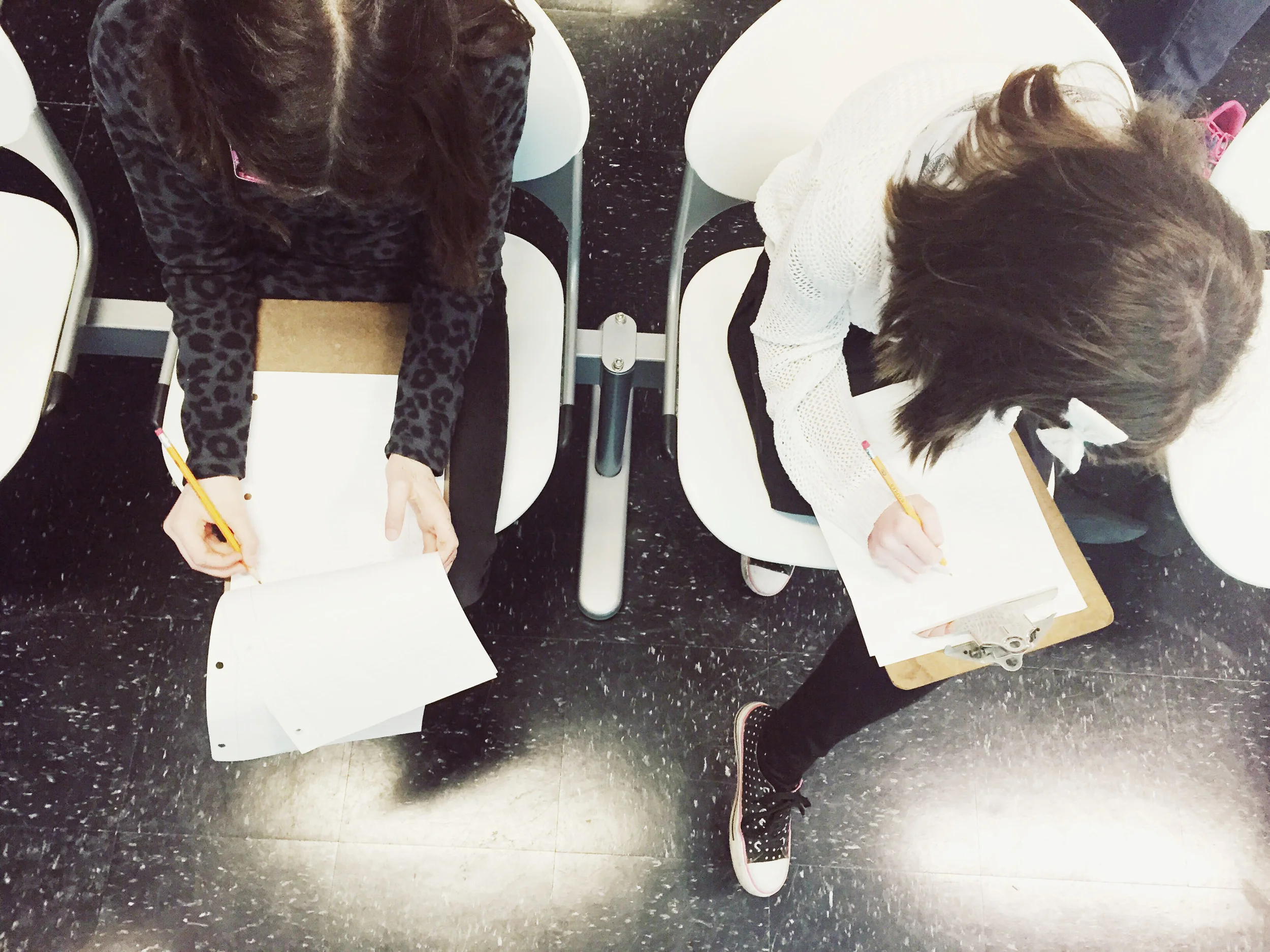

I gave them drills, too, because you've got to take those inspirations and make them tight and zingy and poppy.

Choose an emotion, I instructed. But don't tell us which one. Write a little scene—a character enters a room—and show us how they're feeling in the way they walk, in the verbs you choose, in their expression and unconscious quirks. Then you're going to read aloud, and we're going to guess. GO!

There were clenched fists and slammed doors and faces like the sun.

It can feel like all anybody cares about is money, I said. This is capitalism gone too far. And so sometimes, when you're artistic, and you stand up and say so, the world says: "Oh Yeah? Sure. Who do you think you are?"

I say it with a sneer and they all giggle but they know this is serious stuff. You've got to hold on to differentness like the precious gem that it is. I show Evan's split portrait and ask them to tell me who they think they are—first on the outside, in the usual way that people see. And then on the inside, in their imagination.

On the outside, I am a pretty regular kid, says one, reading in front of a wall-diorama of Neptune. But on the inside I am a hummingbird, putting out fires drop by drop.

We draw and write through life not only for sanity or play or escape, but because when you make space for art, you become a magnet for other people who make space for art. And people like that are weird and rare and fantastic. They do the best stuff. They throw wood onto our fires and they make the room warm. Oddity fuels oddity when everything else is beige.

Illustrators Sydney Smith and Matt James

Illustrator Geneviève Deprés; authors Catherine Austen, Tim Wynne-Jones, and Rina Singh; illustrator Matt James; author Monique Polak; me; and illustrator Sydney Smith at the MASC Young Authors & Illustrators Conference in Ottawa, Ontario. With many thanks to the countless volunteers, organizers, sponsors, and parents who made the most fantastic three days so fantastic for all of us kids.